8-13-2025

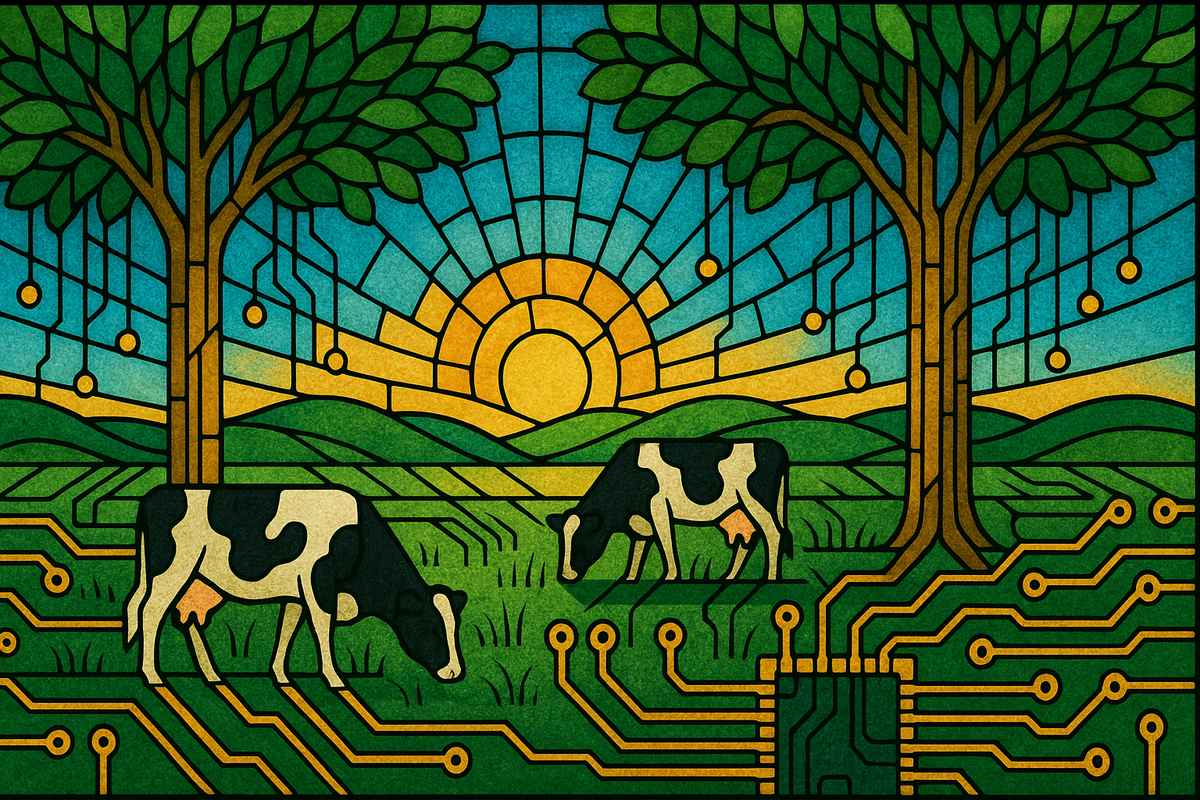

Cathedral’s tree lanes are living infrastructure, each built with primary trees, support trees, hedgerows, and a mycelial network stitching underground. Together they anchor soil, cycle nutrients, guide livestock, and moderate climate. Cathedral is a clock, calendar, and computer. The whole system processes environmental inputs into predictable, regenerative outputs for millennia.

The Cathedral Project stands as a thousand-year silvopasture vision, bound by three uncompromising laws: The land must grow more fertile every year. Productivity must increase every year unless, by doing so, it violates the First Law. Synthetic chemistry cannot be used unless, by not doing so, the First and/or Second Law is violated. On a thousand-acre square of degraded farmland, these rules guide every decision, shaping a system meant to last for generations.

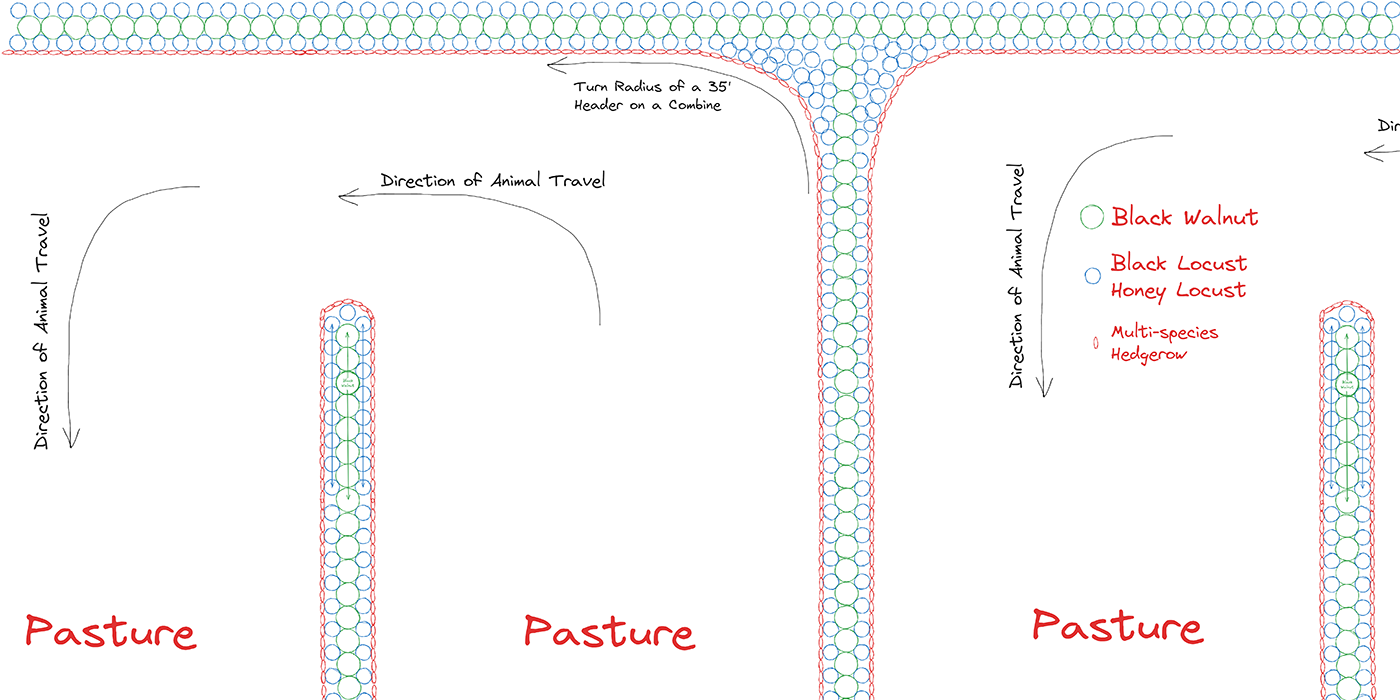

At its edges, Cathedral’s perimeter tree architecture forms the first element of structure. Black walnut trees serve as the primary crop, flanked on either side by black locust and thornless honey locust. These support trees buffer the allelopathic juglone released by walnut leaves, fix nitrogen, supply animal fodder, and produce durable craft lumber. The arrangement forms both a windbreak and a snow trap, capturing winter moisture for spring growth. Every one of the 23 interior tree lanes mirrors this design, with tree rows running north-south to bath in sunlight, half connecting to the perimeter trees at the southern edge and the other half to the northern in an alternating pattern.

On the outer edges of each of these lanes (and on the interior side of the perimeter trees), hedgerows serve as living fences. Built dense enough to be "hog-tight", they keep grazing animals in their lanes while sheltering wildlife and offering berry and other types of production. Hedgerows also create nesting habitat for birds that help control fly populations around livestock, reversing the ecological emptiness caused by decades of fence-row tree removal in industrial agriculture beginning in the 1970's.

Beneath the soil, a more subtle infrastructure thrives. Each planted tree is inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi, linking the entire system in an underground network that transfers water, nutrients, and chemical signals. Biochar, integrated throughout the lanes, acts as a nutrient and water battery, providing surface area for fungi and bacteria while locking carbon in the soil for centuries. Together, this network functions like a living computer, sensing environmental changes, providing linked chemical communications between the roots of all plants in the system, and routing resources where they are most needed.

Over decades, Cathedral’s design supports a rhythm of succession. Black walnut harvests provide both a nut crop and premium lumber, while support trees offer fodder, craftable wood, and fence-posts. Select tree lanes may finish hogs on walnuts or other mast, producing high-value meat. Black Walnut timber harvest cycles are planned to keep nut production between ninety-two and ninety-five percent of potential, replacing felled trees with nursery-grown saplings shaded by remaining support trees. This constant renewal makes the system dynamic rather than static, its changes visible in patterns across the land.

Viewed from above, Cathedral could be considered as a timepiece. The position of livestock reveals the day, the stage of tree replacement shows the year, and the balance of mature and young stands marks the century. From below, it is a vast processing unit, turning environmental signals into predictable, useful outputs. In this way, Cathedral operates as a clock, a calendar, and a computer, built to outlast well beyond the lifetimes of the people who turned the key on that engine.

Cathedral Part I:

Member discussion: